Chinese leaders who dismiss the Hong Kong protesters as spoilt children, unrepresentative of the people, have found an ally in some Western pundits. The same happened when Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 – the Beijing government disparaged this democratic intellectual as a stooge for introducing Western interests in China. Unfortunately this propaganda too-often has the upper hand in Western judgment on China.

Europeans are prone to believing the Chinese do not really know what democracy is, and that they do not long for political freedom. This prejudice has very old roots: in the 18th century, Jesuit missionaries argued in their accounts that China had reached a perfect political equilibrium thanks to an enlightened emperor advised by skillful bureaucrats selected through competitive exams. The Jesuits lied in order to defend their own position as they became members of the imperial court.

The current communist leadership initially tried to seduce the world by promoting the Maoist concept of permanent revolution. After they failed, they returned to a more palatable stereotype: heirs of those past enlightened emperors. Westerners have proved more than ready to swallow the bait when it conforms to ancient preconceptions.

This convergence of Chinese propaganda and Western prejudice is far removed from the real China – either its imperial past or communist present. In ancient times, emperors were fiercely besieged by popular upheavals, dynasties were constantly destroyed and replaced. The ‘enlightened’ bureaucrats usually bought their position and were heavily corrupt. If any continuity can be traced from past to present, it is this constant corruption from officialdom and leaders’ refusal to share their authority.

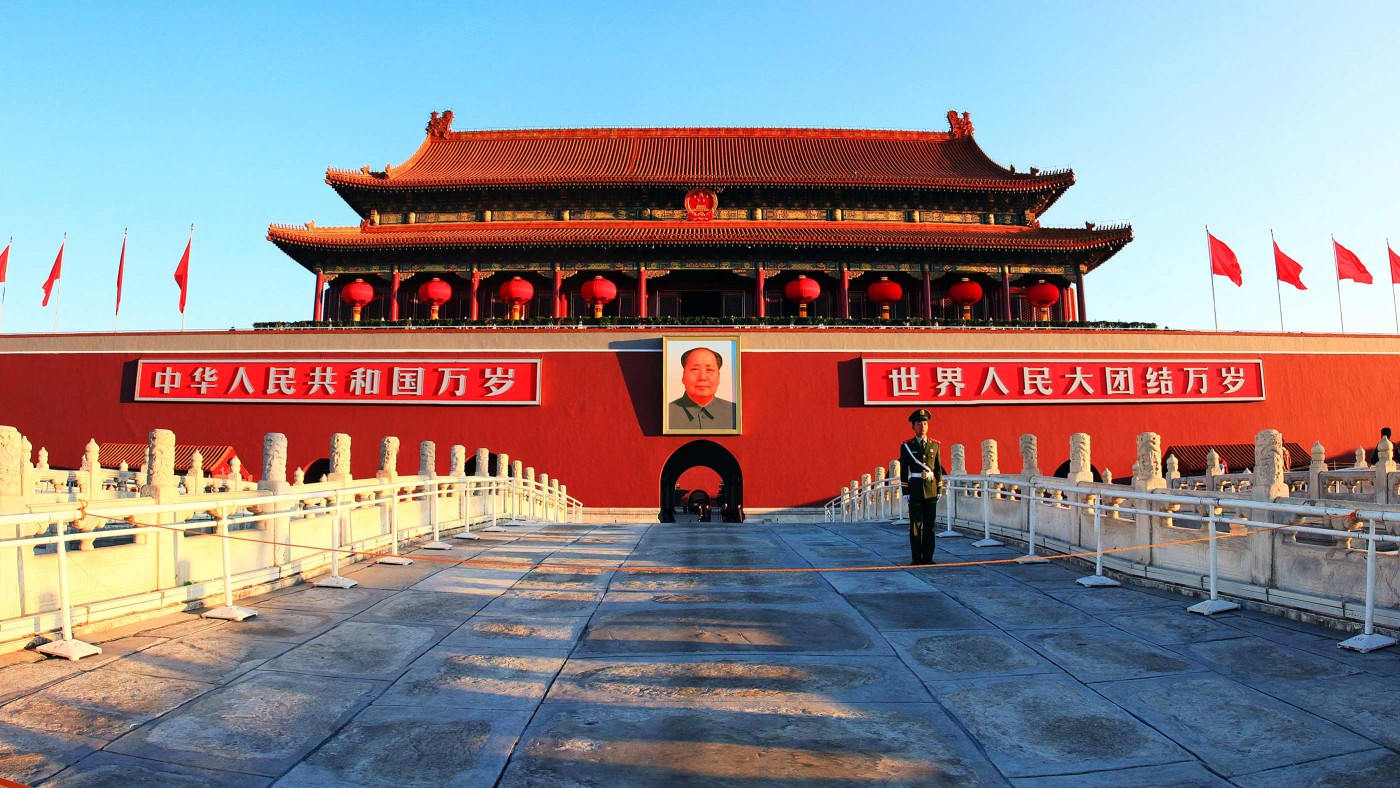

The Emperors tolerated only subservience from subjects and foreign dignitaries. Similarly, the current leadership is always right, even when sharply shifting their policy orientation. Like the emperors, the communist leaders never tolerate criticism and never negotiate with anyone. When the Chinese people start expressing disagreement or mild protest, Communist leaders do not even try to enter into dialogue but send the police or the military to crush the dissent. In 1989, when Beijing students started a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square, the leader Deng Xiaoping sent the military, resulting in the deaths of thousands of peaceful students. Communist Party general secretary Zhao Ziyang was dismissed after suggesting dialogue with the protesters.

Since the Tiananmen massacre, popular discontent has been appeased through high economic growth and increasing opportunity. It has not totally vanished, however. Barely a week goes by in mainland China without some “illegal” event being crushed by police special forces, sometime with the help of government-paid goons. These rebellions usually emerge as a result of Communist bureaucrats who use violence and corruption as the normal way of ruling: local apparatchiks behave exactly like the national leadership, at a more modest level. The only legal way for people to protest against such brutal behavior is to present a written petition to a higher official – a tradition rooted in the imperial past. Just as then, petitioners are often beaten and incarcerated before they reach the higher official. Liu Xiaobo – jailed for eleven years – had been convicted only because he posted a web petition asking for negotiation with the Communist Party in order to build a more democratic regime.

This historical and cultural background explains why the Hong Kong protesters had no alternative but to take to the streets in order to obtain democratic elections, which had been accepted by China when the former British colony was retroceded to Beijing.

To what extent are the protesters or Liu Xiaobo representative or not of Chinese public opinion? Lacking opinion polls or free elections, we do not know the answer. Most Chinese people do not even describe their aspiration in such abstract terms. When one travels throughout China, most people you meet, in all social strata, express the desire to choose freely their local representatives and to have access to independent judges. All blame the corruption of the Communist officials. The most frequent complaint is: “nobody listens to us”.

In Hong Kong today, like Tiananmen yesterday, in Tibet, Xinjiang, and thousands of towns and villages, one can predict with certainty that there will be no true dialogue between dissenters and Communist officials. By refusing debate or negotiation, the Chinese regime puts itself into a corner: violence is the only way out of any controversial situation.

Should we predict an evolution of the regime towards some kind of democracy? Current President Xi Jinping has already closed the door by declaring democracy a Western concept not valid for China. Liu Xiaobo himself has never been optimistic on China’s democratic future: “Several centuries will be needed before the Chinese truly understand the rule of law”. Liu Xiaobo also wrote that the Hong Kong people had been lucky to be colonized by the British, allowing them to bypass history and learn fast the benefits of democracy.

Rebellions in mainland China or the Hong Kong protests are not the major threat against the Communist regime. Economic uncertainty is a more dangerous enemy, starting with a potential real estate bubble. As long as the national currency is not convertible and the Shanghai stock exchange somewhat erratic, the new Chinese middle class has little choice but to invest its huge savings in real estate. Should the value of all these empty buildings crumble, the mostly government-supporting middle class will be bankrupt, unable to pay for healthcare, studies, retirement. “The Chinese”, says Mao Yushi, a free market economist in Beijing, “reluctantly accept to live without liberty but they would never forgive the Communist Party if they were to lose their savings.”

Among all scenarios for the future of China, the status quo is a possibility but certainly it is not the only one: the whole country is like a minefield which could explode anywhere, usually when and where you expect it the least.